Sigma Nu and San Francisco – A Golden Pairing

By Grand Historian Bob McCully (San Diego State)

Everybody loves San Francisco and chocolate! Well, almost everyone. My topics in this column are about two icons of San Francisco: one considered among the seven wonders of the modern world and the other, a famous San Francisco confection. Both celebrated notable anniversaries recently and, more importantly have strong connections with Sigma Nu.

I’ve lived just north of San Francisco for over 40 years. During my professional career, I crossed the magnificent Golden Gate Bridge almost every day. The drive across the bridge is always stunning – whether the sun is shining or the fog is pouring through the Gate. The Bay Area celebrated the 75th Anniversary of the opening of the bridge in 2012.

However, it’s only recently that I learned of the strong connection during the construction of the bridge with Sigma Nu. It involves our two oldest chapters in the West and another on the opposite side of the country, in Pennsylvania. In addition, there’s a connection with two Regents of Sigma Nu and two chapter founders.

My second topic is the story of the second oldest chocolate factory in the United States. This year celebrates the 163rd Anniversary of its beginnings in San Francisco. It’s the Ghirardelli Chocolate Factory, founded in 1852, well before Sigma Nu was even a thought in the mind of our Founders.

Spanning the Golden Gate

John C. Fremont: an American military officer, explorer and politician, named the strait between San Francisco and Marin County. He called it Chrysopylae, or “Golden Gate” because it reminded him of a harbor in Istanbul called Chrysoceras – or the “Golden Horn”.

Dreams of spanning the Golden Gate between San Francisco and Marin County go back to the early days of California’s statehood. Engineers proposed various ideas, but none of them went very far; the task just seemed too daunting. The distance to span, the depth of the channel, the powerful tidal currents, and the high winds made it almost foolhardy to even try. Its fog and rocky reefs resulted in over 100 shipwrecks – not to mention the political battles and special interests that aligned themselves against a bridge ever being built.

Most engineers of the time felt it was physically impossible to construct a bridge over the Golden Gate. The length required to span the strait, combined with the water’s depth (372 feet at its deepest), would be a monumental task if it were even feasible. The powerful tides were a result of the Pacific Ocean, twice a day, pouring millions of cubic feet of water into the San Francisco Bay every second. Countered by the rivers of the Central Valley of California pushing right back into the Pacific twice a day. The rivers drained over 40% of California’s massive interior land mass.

Politics

The political realities of building a bridge across the Golden Gate were just as formidable – some said they made the construction of a bridge the easy part. The City of San Francisco in the 1930’s had a population of around 500,000. Marin County, across the strait, only had a population of around 50,000. Oakland on the east side of the Bay (population 300,000) and the southern part of the San Francisco Peninsula down to San Jose and Monterey, were responsible for most of the commerce with San Francisco. The thirteen counties north of the Gate had tiny populations in comparison.

California’s legislature established the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District (the “GGBHD”) at the end of 1928 to design, construct and finance a bridge. However, only six of the thirteen northern counties voted to become a part of the GGBHD. It’s not surprising when voters realized they’d be required to guarantee the repayment of the construction bonds, whether a bridge got built or not.

Powerful special interests lined up against a bridge as well. The railroads, then operating most of the ferries and barges on the bay, were dead set against it. The timber interests in the northern counties felt new residents would fight against logging the vast redwood forests. Dairymen and ranchers believed that hikers and campers would interfere with the grazing of their livestock. Environmentalists were upset that it would damage the natural beauty of the Golden Gate. The military, which owned the property on both sides of the Golden Gate, opposed the plan because of concern that the destruction of a bridge during wartime could block the harbor. All had strong lobbies and fought strenuously against a bridge. Plaintiffs filed 2,307 lawsuits, and they took over six years to resolve – eventually making it all the way to the Supreme Court.

After all the lawsuits were concluded, and approvals obtained, the GGBHD still had to approve and sell bonds to finance the construction of the bridge – during the very heart of the Great Depression. With minor involvement by the federal government, the District successfully sold the bonds, and the Bridge began construction in 1933. Four years later, at a cost of $35 million and 11 lives, workers completed the bridge – $2 million under the original estimate.

Sigma Nus Step up to the Task

Francis V. Keesling (Stanford) served as Regent of Sigma Nu from 1906-1908. After graduating from Stanford, he earned a law degree and became a successful attorney and civic leader in San Francisco. After an unsuccessful run for governor of California, he successfully ran for the Board of Supervisors, the political body that governs San Francisco. The Supervisors appointed him as one of the first board members of the new GGBHD. In addition, he served as chairman of the crucial building committee for the bridge from 1929-1937, through the bridge’s completion.

Two other Sigma Nus –Henry Westbrook, Jr. (Cal/Berkeley) and Arthur M. Brown, Jr. (Cal/Berkeley) joined Keesling on the twelve member GGBHD board. Westbrook represented one of the northern counties (Del Norte), and Brown represented San Francisco. Effectively 25% of the total board, the three Sigma Nus provided strong and effective leadership in the many daunting, and some thought insurmountable, obstacles faced.

A detailed list of those obstacles is beyond the scope of my column. Suffice it to say, eight years after establishing the GGBHD, on May 28, 1937 the bridge, that many felt was impossible, was opened to auto traffic with the official dedication ceremony. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, from the White House, pressed a telegraph key to open the span officially. Past Regent Keesling, delivered the closing speech at the dedication over national radio and ended with the following:

“We wish that this Golden Gate Bridge may remind the traveler as he leaves or approaches his native shore and also everyone who views it of the liberty and glory of his country where life, liberty, and happiness have so long persisted, so that he may be re-consecrated and, as a result of his “high resolve,” actively devote himself, as he should, to his country’s problems so that the continuity of life, liberty and happiness may be assured.”

A week-long Golden Gate Bridge Fiesta of various events around the city celebrated the opening of the bridge. Several evenings during the Fiesta, a spectacular outdoor pageant dramatized eight episodes from California’s history. Another Sigma Nu, B. Kendrick Vaughn (Cal/Berkeley), later to serve as Sigma Nu’s Regent from 1958-1960, managed this enormous production of 3,000 participants. To provide a sense of its immensity, here’s a section of the promotion for the pageant from the official program for the Fiesta:

“The Span of Gold, with JOHN CHARLES THOMAS, famous baritone and cast of 3000. An embellished Historical Pageant of the History of California from primitive times to statehood – presented in eight stirring episodes climaxing in the breath-taking illumination of the Bridge for the first time – the greatest Pageant ever seen in the West – bringing to life the very spirit of the Fiesta – staged in an incomparable setting in the world’s largest outdoor theatre at Crissy Field in the Presidio.”

Our Eastern Connection

However, Sigma Nu’s involvement was not only at the political level, but also with a critical construction component of the bridge itself. The Art Deco designed bridge rests on a concrete base with a steel structure – 83,000 tons of structural steel to be exact. That steel is where Sigma Nu’s eastern connection comes into the picture.

Sigma Nu installed our Lehigh University chapter in 1885, and two of its charter members were Charles D. Marshall and Howard H. McClintic, II. They both graduated from Lehigh’s young civil engineering program. Shortly after graduating, the two partnered in starting up a steel manufacturing firm, McClintic-Marshall, which, over the next forty years, would grow to become the largest independent steel manufacturing company in the country. Some of their many significant projects included the Marshall Field Store in Chicago; the George Washington Bridge and Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York; half of the floors of the Empire State Building; the Ambassador Bridge linking Detroit and Windsor, Canada and the locks of the Panama Canal. The company was so successful that they were acquired in 1931 by Bethlehem Steel – although they continued operating as McClintic-Marshall for several years after that.

The Bridge District chose the firm to supply the structural steel for the Golden Gate Bridge. McClintic-Marshall manufactured the steel, all 83,000 tons, in the East and shipped it to San Francisco through the Panama Canal over a six-month period to coincide with the building phases.

Sigma Nu’s involvement with the Golden Gate Bridge didn’t end when it opened in 1937. William H. Harrelson (Stanford), entered the first class at Stanford University in 1891. He played quarterback on the football team when Herbert Hoover, later President of the United States, was the team manager. After a successful career as an owner of a large construction company and banker, the District hired him in 1937 as the general manager of the Golden Gate Bridge. He served in the position up until 1942, when he retired for health reasons.

Thus, Sigma Nus played crucial roles in ensuring the Golden Gate Bridge became a reality. Today, more than 75 years later, it remains an endearing image for residents and visitors to San Francisco alike.

Ghirardelli Chocolate Company – 163rd Anniversary

In 1849, during the California Gold Rush, an Italian immigrant, Domenico Ghirardelli, came to seek his fortune in the gold fields. He soon discovered that his road to success was not chasing ore, but utilizing the retail and entrepreneurial experience he developed as a young man. The onslaught of prospectors driven by the dream of striking it rich resulted in an enormous need for supplies of food and tools. Seizing the opportunity, Ghirardelli opened a general store selling supplies and confections in Stockton and later in San Francisco.

Ghirardelli Square – San Francisco.

While growing up in Italy, he apprenticed at an early age to a candy maker. With this knowledge, in 1852 he imported two hundred pounds of cocoa beans and started making chocolates. In the same year, he incorporated the Ghirardelli Chocolate Company in San Francisco. It is the second oldest chocolate company in the United States, behind Baker’s Chocolate in Massachusetts.

Until 1963, descendants of the founder owned and operated the business. Six initiates of our Beta Psi Chapter at the University of California, Berkeley were among those descendants.

A Timely Discovery

One of the reasons Ghirardelli was so successful is due to a monumental discovery, made entirely by accident. Prior to the mid-1860’s, chocolate was a very perishable commodity. Due to its high fat content, it was not transportable long distances without spoiling. Thus, the geographical market for chocolate manufacturers was small.

By chance, bags of chocolate paste were left hanging and forgotten in a hot room at the Ghirardelli factory. Over time, fat seeped out of the bags leaving a greaseless residue behind. Ghirardelli found that this residue could be ground, sweetened and easily made into hot cocoa and other items. The miracle was that it was nonperishable and could be shipped great distances. With the opening of the first transcontinental railroad several years later, Domingo Ghirardelli hit the pay dirt he never found in his short time in the gold fields of California.

Ghirardelli chocolates were very successful up until World War II. However, during the war, the military entered into a contract with Hershey’s to provide all the chocolate bars for troops in Europe and the Pacific. Due to that agreement, 75% of the chocolates consumed during the war were made by Hershey’s and transformed the country into lovers of Hershey’s chocolates. This transformation resulted in a demise in the fortunes of the Ghirardelli company.

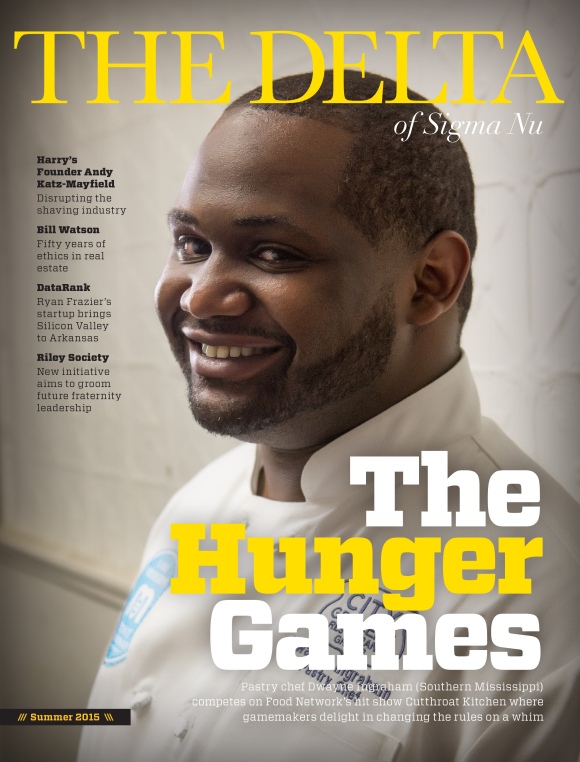

Domingo Ghirardelli’s Grandsons

After Domingo Ghirardelli retired in 1889, his three sons took over operations of the business. One of the sons, Louis, also had three sons – Alfred, Louis and Harvey, who attended the University of California at Berkeley. They all initiated into Sigma Nu and went on to run the company in various capacities.

Alfred Ghirardelli (Cal/Berkeley), the oldest son of Louis initiated into Sigma Nu in 1902. He graduated with a degree in Mechanical Engineering with the “earthquake class” of 1906 – so called because their final months were interrupted in April, 1906 by the Great San Francisco Earthquake. Alfred was at the Sigma Nu house when the earthquake struck at just after 5:00 am. He was extremely concerned about the status of the factory, housed then in brick buildings in San Francisco. He hired a boat to ferry him across the Bay and found that the facility was largely intact and had sustained only minimal damage.

After graduation, due to his engineering training, he worked with the company’s chief engineer. In 1944, upon the retirement of his uncle, he took over the presidency. He served as president until 1955 when his health declined, forcing him to retire.

Alfred’s brother, Louis L. Ghirardelli (Cal/Berkeley), followed his older brother to Berkeley and was initiated into Sigma Nu in 1906. He also later joined the family company and due to his outgoing, warm and gregarious nature eventually was put in charge of sales for the business.

Their youngest brother, Harvey T. Ghirardelli (Cal/Berkeley), initiated into Sigma Nu in 1909. He was detail oriented by nature, and once he moved into the family’s operations, he became the plant manager. Upon Alfred’s retirement as president in 1955, Harvey took over the presidency.

A fourth grandson of Domingo was Virgil W. Jorgensen (Cal/Berkeley), initiated in 1907. He was close to his cousins and worked for the Ghirardelli company for many years.

The remaining two Sigma Nu connections to the Ghirardelli chocolate company were Robert O. Ghirardelli (Cal/Berkeley), initiated in 1932 and Chris W. Anderson (Cal/Berkeley) initiated in 1939. Robert, the son of Harvey T. Ghirardelli, was a legacy when initiated into the chapter. Although he worked for the company, he had an artistic bent that kept him from being heavily involved in the management of the firm. When he died, in 1990, he was the last descendant of Domingo Ghirardelli to bear the family name. Chris Anderson also worked for the company but did not play a significant role in its operations.

The Ghirardelli family sold the company in 1963, ending their more than 100-year connection with the business. The Swiss company Lindt & Sprungli, now owns Ghirardelli Chocolates. It has once again risen to be part of one of the top chocolate manufacturing firms in the world. Thanks to the Ghirardelli family, it will always be a sweet reminder of San Francisco.

The next time you visit San Francisco, appreciate the beautiful Art Deco Golden Gate Bridge with its surrounding natural beauty and pay a visit to Ghirardelli Square. As you enjoy these San Francisco landmarks, don’t forget their connection with Sigma Nu.